SWEDISH SOUTH ASIAN STUDIES NETWORK

Bhutan impressions, from a journey Phuentsholing – Thimphu, Sunday 27 November

This is tropical green – all kinds of crops can be grown, rice,

fruits and vegetables, but only on miniscule plots on terraces of the

mountain slopes and for family use. Women inherit all property, including

land, so no male land grabbing here! Little is exported – we know

of only apples. But the forest is rich and if you can log it and cart

it somewhere, it is certainly worth it. But that is a royal prerogative,

all forest belong to the state. The real asset in these mountains are

the streams, rivers and waterfalls – the most important source of

income to the government and those sharing in state incomes is export

of hydro-electric power to India.

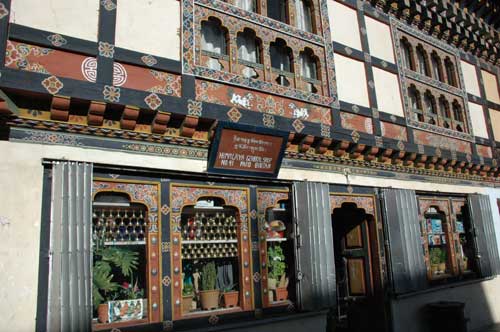

Houses have an appearance like in many mountain countries, like Switzerland

or Austria, with flatly sloping roofs but there is a distinct Himalayan

touch with all the woodwork decorations. There must be a lot of very good

carpenters around.

Not all houses are like that. We find rows of shacks belonging to, it

is said, those Llotshampa Nepalese people who are still working and living

here.

|

| National Museum in Paro |

The king guides the country

With a population of about 7 lakhs this is of course a very small humanity

to govern for the Bhutanese King, the fourth in line since the creation

of an all-Bhutan kingdom in 1907. He guards the Buddhist tradition of

most Bhutanese and he now guides the country into a negotiated modernity

that is rather unique in South Asia, not to speak of the rest of the world.

In the early 1990’s the king declared a Bhutanese code of conduct,

the so-called Driglam namzha (more

information). While at work, in offices or factories, citizens should

wear a national dress, which we now see on many people around, increasingly

so as we approach the capital Thimphu. It is not really a uniform, however,

and we see many different patterns and colours of the dress.

Second, all should speak the national language Dzongkha. It was supported

by most people and seems well anchored in the Bhutanese ethnos. The Lhotshampa

minority though, of Nepalese origin but since generations in Bhutan, objected

and mobilised against it with some violence in the end. As a result, about

a lakh of these people are now staying in refugee camps on the other side

of the border to Nepal.

The king is also the guardian of the Himalayan Buddhism practiced here,

but with a ‘division of labour’ with the Chief Abbot of Lama,

who is the spiritual head and with the same status as the king. All inhabitants

are not Buddhists, but most are however divided by tribal distinctions

and languages. A decisive minority is also Hindu, whether hailing from

Nepal or parts of northern India.

New constitution is coming

A new constitution is in the making, allowing for a constitutional democracy

and freedom of religion. Negotiations are going on about the return of

the refugees in camps in Nepal.

We meet a lorry representing Coca-Cola Bhutan. We see people with modern

consumer goods all around but mixing it with a distinct everyday traditional

Buddhist culture. Internet came late here as did TV. Both of these modern

media were introduced in 1999 and there is now a national channel with

English subtitles. However, satellite TV is also there and the Bhutanese

can take the whole world into their drawing rooms.

Tourism is still much limited. It is more or less restricted to an up

market exclusive tourist inflow via tour groups, and each tourist must

pay about 220 dollars a day, all inclusive.

The state of Bhutan owns all rivers, forests, and mineral resources and

the environment is protected by strict rules about logging prescribing

that at least 60 per cent of the Bhutan territory should be covered with

forest. As we approach the central part of the kingdom, we can see that

the higher areas, where pine trees grow, are less fully covered with forests,

and we understand that this may be a necessary protective measure. However,

nothing like the devastating deforestation that has taken place in other

parts of the Himalaya can be seen here.

Tobacco is banned, and smugglers from India have a hard time, since the

Bhutan police and army is now well equipped to deal with troublemakers

after its build up to successfully fight Indian tribal extremist groups

hiding within Bhutan borders in the 1990s.

|

| The centre of power in Bhutan, the dzong in Thimphu housing the offices of the King as well as of the Chief Abbot (Je Khenpo) who is chosen from among the most learned lamas of the country. He enjoys an equal rank with the King. |

How come such an autonomous approach to national borders, culture and economy has been possible in South Asia on the border to China? Can it be preserved in this era of globalisation?

India and China seem to have held each other at bay in this case, neither allowing the other any interference. Bhutan, has also not had any decisive internal challenge to its system of rule, like that in Sikkim, which simply couldn’t handle Nepalese uprisings in the seventies and, therefore, asked for Indian help. Sikkim was immediately annexed by India in 1975, and China couldn’t really stop it.

More interestingly though. Has Bhutan found a formula also for preserving difference in a world of equalising global forces of commerce, culture and politics? It really remains to be seen, but should be worth a close follow up by all those people who value cultural roots and a sound environment.

SASNET - Swedish South Asian Studies Network/Lund

University

Address: Scheelevägen 15 D, SE-223 70 Lund, Sweden

Phone: +46 46 222 73 40

Webmaster: Lars Eklund

Last updated

2006-02-13