SWEDISH SOUTH ASIAN STUDIES NETWORK

Reflections from the Seminar |

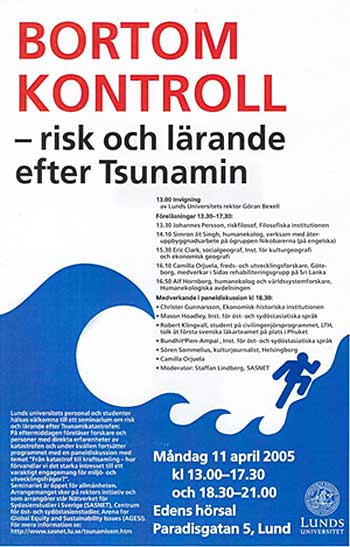

Beyond Control – Risk and Learning After the Tsunami |

held at Lund University, Monday 11 april 2005, 13–21.

|

Summary

by Sabina Andrén, AGESI:

Summary

by Sabina Andrén, AGESI:

After the earthquake and the tsunami in the Indian Ocean, Lund University’s

Vice-Chancellor Göran Bexell

appointed a working group to propose how the university could

pay attention to the natural disaster.

|

One of the suggestions was to organise an open seminar where researchers and other experts would give their view on risks and learning based on the Tsunami disaster. This seminar was held on Monday 11 April 2004. Collaborating partners to arrange this event was Swedish South Asian Studies Network (SASNET), Centre for East- and South-East Asian Studies and Arena for Global Equity and Sustainability Issues (AGESI).

The seminar was introduced by Vice-Chancellor Göran Bexell himself. In his speech he described the seminar as a part of Lund University’s profile on global sustainable development. He also underlined the importance of interdisciplinary meetings and co-operation between faculties on this subject.

Concepts of risk and control

Johannes Persson, Associate

Professor at Lund University’s Department

of Philosophy, was the first speaker in the afternoon session.

As a philosopher he elaborated on ”The concepts

of risk and control”. What people consider as a risk depends

not only on the specific object that is concerned, but also on the possibilities

of risk management and protection from this risk object.

When the person or the society has total control, then the risk is zero.

On the opposite, when there are no possibilities to influence the course

of events at all, risk has changed into destiny. It is between these polarities

we, as individuals and as societies, are forced to live. We also have

to separate between two types of risks: risks as general categories and

risks as individual events. When the Tsunami reached the shores of the

Indian Ocean, it could no longer be considered as a risk, because it was

already an actual and on-going event that couldn't be controlled.

When the person or the society has total control, then the risk is zero.

On the opposite, when there are no possibilities to influence the course

of events at all, risk has changed into destiny. It is between these polarities

we, as individuals and as societies, are forced to live. We also have

to separate between two types of risks: risks as general categories and

risks as individual events. When the Tsunami reached the shores of the

Indian Ocean, it could no longer be considered as a risk, because it was

already an actual and on-going event that couldn't be controlled.

For the individuals who were hit by the Tsunami, we can no longer speak

of risk, but of a fact. But if we look at Tsunamis as a general phenomenon,

then they are certainly a risk, because the individual as well as the

society can make choices that will create different risk images. For example,

a Tsunami warning system or other precautionary measures for those living

very near to shore, would have reduced the risk for Tsunamis as general

phenomena. One of the things that we can learn from the Tsunami in 2004,

is that while we as individuals to some extent can reduce our exposure

to risk, political and collective actions of risk management are very

important. At the same time even modern societies and individuals as modern

persons have to live with the fact that risks will always exist and can

never be completely controlled.

Nicobar Islands worst affected

The next speaker was Simron jit Singh,

Researcher and Lecturer at the Institute

of Social Ecology, University of Klagenfurt in Vienna. Singh defended

his PhD at the Department of Human Ecology in Lund on ecological unequal

exchange using the Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal as a case (more

information on his dissertation). The Nicobars, part of the Indian

Union territory of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, are largely inhabited

by an indigenous community called the Nicobarese. They were heavily affected

by the Tsunami.

Simron, who spoke on the effects of the Tsunami

to the Nicobar Islands, arrived to the seminar straight from the

Nicobar Islands, where he had been working with the local Tribal Council

in the first phase of rehabilitation and reconstruction after the Tsunami.

Emotionally affected and upset by the effects of the natural disaster,

Singh showed unique photographs from the totally devastated islands. Being

close to the epicentre and with people living on the coastal zones were

one of the most severely affected areas in the Indian Ocean. Nearly one

third of the inhabitants were swept away by the waves, while the surviving

are left homeless, propertyless, and without an economy to support them.

Simron, who spoke on the effects of the Tsunami

to the Nicobar Islands, arrived to the seminar straight from the

Nicobar Islands, where he had been working with the local Tribal Council

in the first phase of rehabilitation and reconstruction after the Tsunami.

Emotionally affected and upset by the effects of the natural disaster,

Singh showed unique photographs from the totally devastated islands. Being

close to the epicentre and with people living on the coastal zones were

one of the most severely affected areas in the Indian Ocean. Nearly one

third of the inhabitants were swept away by the waves, while the surviving

are left homeless, propertyless, and without an economy to support them.

The Nicobarese economy, prior to the Tsunami, was largely subsistent,

derived by hunting and gathering, fishing and the export of copra (dehydrated

coconut) in exchange for rice, cloth and other daily commodities. Singh’s

description of the national and international assistance was very critical.

The Indian authorities were very slow to undertake rescue and deliver

relief to the affected people on the islands. Insensitive interventions,

lack of co-ordination, and little understanding of the special cultural

and ecological context have been serious problems in the post tsunami

phase. Indigenous leaders played a vital role in the rescue operations,

while state representatives and NGO officials operated with different

logics and means. According to Singh, the NGOs are involved in a kind

of ‘bidding ground’ to the assistance activities.

In this ‘Eden for NGO’s”, a peculiar ‘market place’

for state and NGO competition has also emerged. While the whole process

of rehabilitation and reconstruction has been stalled by these conflicts,

Singh puts hope in the work of the local tribal council, that attempts

to coordinate a comprehensive reconstruction plan for the Nicobar Islands

to be developed in consultation with the people. The plan aims to rebuild

the unique culture and livelihood of the islands without destroying traditional

forms of self-reliance, the social system and local leadership, and the

ecologically sustainable management of the natural resources of the islands.

Eric

Clark, Professor at Lund University’s Department

of Social and Economic Geography, spoke about: ‘The

Second Wave – Beyond Control?’ As a researcher in Social

Geography he has paid special attention to processes of gentrification,

which involve shifts in land use and displacement of land users associated

with redevelopment. One example is the way attractive areas on tropical

islands are bought by socio-economically powerful groups whose visions

of hotels, restaurants and luxurious residencies stand in stark contrast

to the visions of present land-users. Gentrification is a general and

worldwide phenomenon. Poor and marginalized groups are unsettled from

their homelands by a process of market economy logics and the strength

of those who have access to capital and power.

Eric

Clark, Professor at Lund University’s Department

of Social and Economic Geography, spoke about: ‘The

Second Wave – Beyond Control?’ As a researcher in Social

Geography he has paid special attention to processes of gentrification,

which involve shifts in land use and displacement of land users associated

with redevelopment. One example is the way attractive areas on tropical

islands are bought by socio-economically powerful groups whose visions

of hotels, restaurants and luxurious residencies stand in stark contrast

to the visions of present land-users. Gentrification is a general and

worldwide phenomenon. Poor and marginalized groups are unsettled from

their homelands by a process of market economy logics and the strength

of those who have access to capital and power.

‘The second wave of risk comes when what is disaster for one person,

becomes an opportunity for another’ Eric Clark pointed out. What

will happen on the islands and coastlands of the Indian Ocean? Will the

local and small scale fishing populations be driven away to be replaced

by tourist hotels and recreation areas for the urban rich? Is this kind

of process a necessary evil, the price for ‘development’ in

these often relatively poor countries of the region? There are evidently

many ‘top-down’ measures and signs of gentrification in the

‘post Tsunami phase’. But Eric Clark also directed the seminar

participants’ attention to other actors that do not represent large

scale and financially strong interests. The reconstruction of the shores

and islands of the Bay of Bengal is not without opportunity for these

groups. But at the same time, the ‘colonial presence’ and

the huge inequalities with regard to access to power and capital is a

threat to socially and culturally as well as ecologically sustainable

post Tsunami reconstruction.

War or peace in Sri Lanka after the Tsunami?

Next

speaker was Camilla Orjuela,

Researcher at the Department of Peace and Development

Research (PADRIGU) at Göteborg University. She had recently returned

from a month’s visit to Sri Lanka where she took part in a study

organized by the Sri Lankan government and international donors on how

to implement post-tsunami reconstruction. The east and south coasts of

Sri Lanka were severely hit by the Tsunami. About 30 000 people died and

whole areas were devastated.

Next

speaker was Camilla Orjuela,

Researcher at the Department of Peace and Development

Research (PADRIGU) at Göteborg University. She had recently returned

from a month’s visit to Sri Lanka where she took part in a study

organized by the Sri Lankan government and international donors on how

to implement post-tsunami reconstruction. The east and south coasts of

Sri Lanka were severely hit by the Tsunami. About 30 000 people died and

whole areas were devastated.

Rebuilding Sri Lanka is dual challenge Besides the massive reconstruction,

there is also the conflict between the government and the Tamilian forces

in the north and east part of the country to take into consideration.

Camilla Orjuela gave a detailed report about the

current situation in Sri Lanka, a situation which unfortunately

shows slow progress in moving from first aid assistance to long term reconstruction

and rehabilitation. Local people experience a lack of information and

opportunity to influence the process. The Sri Lankan government exercises

a centralized power from the capital in the south west.

In combination with the political conflict this adds another problem to

an already vague democratic situation. If the properties and houses lost

in the Tsunami are to be compensated for, will this also be the case for

property and houses destroyed and lost because of the conflict? What is

the reconstruction of the coast near villages going to look like? What

is to be rebuilt and on what level of material standards? What kind of

‘development’ will be implemented in the post Tsunami reconstruction

of Sri Lanka? Camilla Orjuela gave a disturbing picture of the struggle

between national and international actors and their large scale plans

on the one hand, and the local and small-scale population that must live

with the consequences on the other.

How westerners reacted to the effects

The

last speaker in the afternoon session was

Alf Hornborg, Professor at the Human

Ecology Division. As a cultural anthropologist and world system researcher,

Hornborg presented some reflections on how we, as

modern persons in the industrialized Western countries, reacted on the

effects of the Tsunami. While as a seismic sea-wave it was obvious

on our TV-screens, it also created what could be called ‘an emotional

tidal wave’ in the global community, comparable to that following

9/11. Our perceptions of identity and security were fundamentally shaken.

How could this disaster happen? Was nature really so beyond control? And

as Europeans and especially Swedish tourists were among the victims: how

could this be allowed to happen to our own relatives and friends?

The

last speaker in the afternoon session was

Alf Hornborg, Professor at the Human

Ecology Division. As a cultural anthropologist and world system researcher,

Hornborg presented some reflections on how we, as

modern persons in the industrialized Western countries, reacted on the

effects of the Tsunami. While as a seismic sea-wave it was obvious

on our TV-screens, it also created what could be called ‘an emotional

tidal wave’ in the global community, comparable to that following

9/11. Our perceptions of identity and security were fundamentally shaken.

How could this disaster happen? Was nature really so beyond control? And

as Europeans and especially Swedish tourists were among the victims: how

could this be allowed to happen to our own relatives and friends?

At the same time as feelings of deep distress and dismay are understandable,

there are also some important lessons to be learned from the Tsunami.

Firstly, nature has other features than just being a relaxing domain for

leisure and consumption. Nature is not only beautiful and enjoyable, but

frightening and wild. Even if human beings have made progress in the exploitation

of almost every single ecosystem on the planet, nature remains inherently

beyond our control. Secondly, the Tsunami uncovered what Hornborg called

the political geography of security.

Even if the wealthy nations of the so-called North are expected to provide

welfare and security for their citizens, increasing mobility in a globalized

world has made it more difficult to keep danger out (witness 9/11) and

to keep citizens securely at home. Moreover, the prosperity of these nations

is intimately linked to a world system of unfair distribution of resources

and unequal trade relations. The technological security offered by the

welfare state can thus only be local. Globally we can expect increasing

levels of insecurity, often as the flip side of the North’s technological

struggles to increase security at home.

Panel discussion

The seminar ended with a panel discussion between researchers and persons

with experiences from the Tsunami catastrophe. Staffan

Lindberg, Professor at the Department

of Sociology (and Director for SASNET) and moderator of the seminar,

introduced the theme of the evening discussion: ”From

Disaster to Mustering of Strength. How Do We Transform the Strong Interest

into a Strong Commitment for Environmental and Development Issues?”

Staffan raised some questions for the panel and the audience to discuss:

What can we learn from the Tsunami and perhaps do better in the future?

What possibilities are there to strengthen and co-ordinate efforts in

support of an ecologically and socially sustainable development in the

region? Some answers to these questions, and others were discussed by

the panel and the audience. The panel members also gave a short presentation

of their view on lessons to be learned from the Tsunami.

Christer Gunnarsson, Professor at the Department of Economic History, advocated the need for faster and stronger development in terms of increased wealth from economic growth and productivity. Even if the risk of unequal benefits from economic growth and increased production of goods and services has to be properly managed at a political level, the threat is not development, but rather the lack of development in many of these countries, according to Gunnarsson. It remains to be seen if the national authorities and the international community are able to monitor such a ‘positive development’ in the region.

Mason

Hoadley, Professor at the Department

of East and South-East Asian Languages (photo to the right),

reported from Indonesia, one of the most affected countries in the region.

In the very poor and war-torn coastal areas north of Sumatra, the Aceh

region, the earthquake and the Tsunami almost completely destroyed the

social structure. The Indonesian government has launched an assistance

plan for relief, rehabilitation and reconstruction. But the implementation

has yet to take place, and there is also some doubt whether the huge amounts

of money will be spent on efficient and targeted assistance to the people.

Mason

Hoadley, Professor at the Department

of East and South-East Asian Languages (photo to the right),

reported from Indonesia, one of the most affected countries in the region.

In the very poor and war-torn coastal areas north of Sumatra, the Aceh

region, the earthquake and the Tsunami almost completely destroyed the

social structure. The Indonesian government has launched an assistance

plan for relief, rehabilitation and reconstruction. But the implementation

has yet to take place, and there is also some doubt whether the huge amounts

of money will be spent on efficient and targeted assistance to the people.

Mason Hoadley questioned whether the traditional political and administrative

bureaucracy is able to adopt the new ideas of ‘public management’,

for example to use methods for democratic participation, bottom-up policies

and transparency of information.

Joining the panel was Robert Klingvall,

student at Lund Institute of Technology and

often visiting Thailand as his mother and many relatives are Thai. Robert

Klingvall was in northern Thailand when the Tsunami hit the southern coasts.

He immediately went to the area and worked as an interpreter for a Swedish

medical team. Robert Klingvall gave an intimate and detailed picture of

the chaos and panic that characterized the situation in Phuket during

the first days after the Tsunami. He described the difficult work of the

medical team, and criticised media for not giving a comprehensive and

balanced picture of the very complex situation that faced the victims

and for those trying to assist and help.

Bundhit

Pien, Lecturer at the Department of East

and South-East Asian Languages, also described the Thai situation

but from a social perspective. Tsunamis are nothing new in the history

and experience of the Thai people. And despite of the warnings that were

received from the Pacific Ocean Tsunami warning system some 75 minutes

before the actual tidal wave reached the coast lines of Thailand, no warnings

were sent out to the coast near local villages and tourist resorts.

Bundhit

Pien, Lecturer at the Department of East

and South-East Asian Languages, also described the Thai situation

but from a social perspective. Tsunamis are nothing new in the history

and experience of the Thai people. And despite of the warnings that were

received from the Pacific Ocean Tsunami warning system some 75 minutes

before the actual tidal wave reached the coast lines of Thailand, no warnings

were sent out to the coast near local villages and tourist resorts.

Are the Thai people risk loving and believers in fate? Or is it a question

of a corrupt bureaucratic system that will risk anything except to threaten

the profitable tourist industry and the image of Thailand as a safe and

strong country? Bundhit Pien asked for correct data and for the true picture

of the whole course of events. He urgently requested Sweden and the international

community to demand transparent information from the Thai government on

the issue.

Are the Thai people risk loving and believers in fate? Or is it a question

of a corrupt bureaucratic system that will risk anything except to threaten

the profitable tourist industry and the image of Thailand as a safe and

strong country? Bundhit Pien asked for correct data and for the true picture

of the whole course of events. He urgently requested Sweden and the international

community to demand transparent information from the Thai government on

the issue.

Sören Sommelius,

writer and journalist at the Swedish newspaper Helsingborgs Dagblad (photo

to the right), commented on the role of media. Western media covers

only the parts of the world which are connected to western economical

interests. So almost nothing was in the beginning reported from the Indian

east coast on the effects of the tsunami, as the consequences for multimillion

city Chennai. Small Scandinavian tourist resorts were heavily covered.

As Swedes we have a personal interest in the situation in the resorts,

but the bias was nevertheless obvious to every observer. Sören Sommelius

painted an alarming picture of the state of the media reports. Every day

around a hundred thousand humans die from hunger, poverty and diseases

that we have the possibility to cure. But these continuous disasters do

not create big headlines. Media, as well as the university, has an important

role to play in creating a true ‘global arena’ for information

and communication about the state of the world.

Sabina Andrén, AGESI

The post-Tsunami seminar was also covered by the regional newspapers: The journalist Stig Larsén wrote an article in Sydsvenskan on 12 April 2005, called ”Tsunamihjälp får skarp kritik”. Read his article (as a pdf-file, in Swedish).

Sören Sommelius, participant in the seminar himself, also wrote an article called ”Hur länge varar vårt intresse för offren?”, published in Helsingborgs Dagblad on Wednesday 13 April 2005. Read his article (as a pdf-file, in Swedish).

Finally the seminar was covered by Lund University’s journal Lunds Universitet Meddelar (LUM) in its 27 April issue. Read Ulrika Oredsson’s interview with Simron Jit Singh, an article called ”Fel hjälp kom till Nikobarerna” (as a pdf-file, in Swedish).

SASNET - Swedish South Asian Studies Network/Lund

University

Address: Scheelevägen 15 D, SE-223 70 Lund, Sweden

Phone: +46 46 222 73 40

Webmaster: Lars Eklund

Last updated

2006-01-27